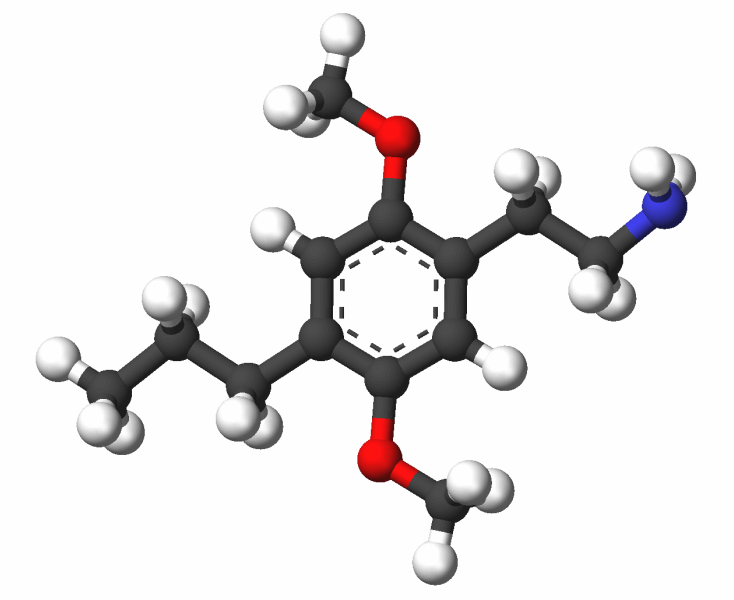

Psychedelic research for eating disorders is in its infancy. Take the 2022 King’s College trial on psilocybin for anorexia, a potentially game-changing clinical trial to assess whether the psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms could help to treat anorexia. Dr Hubertus Himmerich, a clinical senior lecturer in eating disorders at KCL, who is leading the trial, said he believed that psilocybin could help to tackle low moods and obsessive-compulsive thinking in patients:

Psilocybin has been shown to have an effect on the serotonin system. This is important for the psychedelic effect, but also for regulating mood,” he told the Standard. “There have been previous observations in anorexia patients that have found that, after taking psilocybin, they have been less anxious and not restricted calorie intake as much.

He said that he hoped psilocybin would also help to “open up new perspectives” for patients:

The problem with psychotherapy and anorexia nervosa is that patients become stuck in a certain way of thinking… the psychedelic experience could give them a way to see the world through different eyes.

Conclusions from the study were quite positive. Psychedelics like psilocybin temporarily mute the default mode network (DMN), a brain circuit linked to self-criticism. In theory, this could soften anorexia’s relentless “voice” telling patients they’re not thin enough. The KCL study found reduced DMN activity in anorexia patients post-psilocybin.

While heralded as another potential cure-all MDMA trials for binge eating disorder (BED) are sorely lacking. “We have some good info suggesting that this could be one of the more important uses of MDMA,” says Rick Doblin, executive director of MAPS. “But because of the lack of funding, we have not actually started any formal studies.” While MAPS studies are planned for the near future, the current lack of conclusive data makes any claims of MDMA’s efficacy as a treatment are as yet unproven.

The eating disorder community at large certainly isn’t completely sold. Beat, the UK’s leading eating disorder charity, warns of dangerous oversimplification in psychedelic hype, urging caution and emphasising the need to stop focussing solely on the management of or curing of symptoms, but tackling the societal reasons behind the disorder.

Some indigenous practitioners echo this sentiment. Psychedelics are said to reveal truths, but truths can destroy you if you’re not ready. Western trials skip the years of preparation required to truly appreciate the effects of these substances, and their wider ramifications.

The science isn’t useless, there is certainly some promise, but it is far from a saviour. Until studies address eating disorders’ tangled roots (trauma, genetics, systemic fatphobia), psychedelics risk becoming another tool to “fix” patients, rather than tackling the culture making them sick.

The irony of this would be the fact that psychedelics hold within them the potential to dramatically alter the culture making people sick in the first place.

share your toughts

Join the Conversation.