The weakest part of Muraresku’s argument is his conclusion that a psychedelic Dionysian cult persisted in the Christian religion. His characterisation of Jesus as a new Dionysus – a figure involved in ecstatic, intoxicated rituals – finds some scholarly foundation. Dennis MacDonald has documented how the Gospel of John deliberately employs Dionysian tropes: the water-to-wine miracle, the identification of Jesus with the vine, and the symbolic consumption of divine blood. Yet this does not mean that the Christians took all of Dionysian religion with them. As Jules Evans notes, John’s Jesus is described in numerous metaphors, like being Bread, the Door, and the Good Shepherd.

It is worth reviewing the New Testament in detail.

The Gospel of John may deploy Dionysian imagery as sophisticated theological intertextuality (much as The Gospel of Mark makes use of Homer, or Luke-Acts the works of Josephus), but this is fundamentally different from claiming that early Christians replicated the Dionysian mystery cult’s sacramental pharmacology. “His wine had to be just as unusually intoxicating, seriously mind-altering, occasionally hallucinogenic, and potentially lethal as all the holy wine from Galilee and Greece”, Muraresku exaggerates. “And a shot of his “True Drink” had to transport you”.

The Gospel of John is widely dated to the late 1st century or early 2nd century – decades or generations after Jesus’s ministry. If John reflects later theological elaboration shaped by Paulinism and Alexandrian metaphysics (as most scholars argue), it cannot serve as evidence for apostolic-era practice. While controversial, Hugo Méndez’s recent work plausibly contends that the entire Johannine corpus (the works later attributed to the Apostle John, Son of Zebedee) comprises a series of forgeries, much like the dozens of other circulating texts of the era that variably entered the New Testament. Many letters attributed to Paul have been determined to be fraudulent, as have the two letters of Peter.

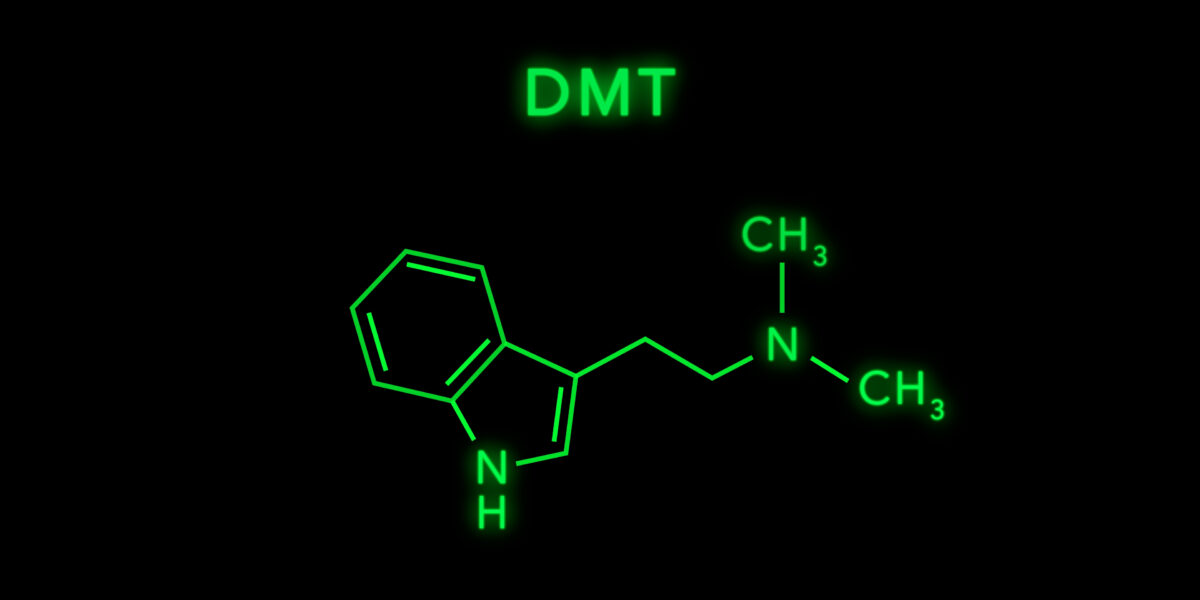

Paul presents a complex data point in Muraresku’s case. Paul’s letter to the Galatians presents Paul explicitly denouncing pharmakeia (the root word of pharmaceutical) (5:20) as incompatible with Christian life. The Book of Revelation, likely authored by a competing Jewish anti-Pauline sect, similarly condemns pharmakeia as grounds for exclusion from the new Jerusalem (22:15). This may stand as worthwhile evidence for some heterodox psychedelic practice. This is why it is odd that Muraresku leaves these two citations unmentioned.

One problem is that the Greek pharmakon (φάρμακον) had a radically unstable semantic range. It could mean a healing drug, a lethal poison, a magical amulet, a dye, a chemical trick, or metaphorically, a “corruption” of doctrine. Muraresku makes much of a pharmaceutical interpretation of the word. This means that Muraresku’s case is contradictory. He asserts that the authors of Revelation and the possibly forged Fourth Gospel are “usually” considered the same figure. The identity allows Muraresku to strengthen a connection to a Dionysian psychedelic community in Ephesus, to whom Ignatius was apparently writing with his message of the “medicine of immortality” (more on this shortly). The hypothetical Johannine community is traditionally located in Ephesus – though traditional attestations were recorded decades after the act – while Patmos is nearby.

Muraresku cites Revelation along with a spate of non-canonical texts as indicative of a hallucinatory core of Christian practice. Indeed, Revelation is perhaps the most psychedelic text in the New Testament. He entertains the idea that John’s Eucharistic verses are “addressing a group of female visionaries getting high in Ephesus”, which allows him to “finally understand his Gospel”.

For one, the Fourth Gospel is never attributed to a ‘John’. The Fourth Gospel is anonymous, as well as being the result of multiple versions recorded over centuries. The sayings of Jesus contained in its parchments differ so wildly from those recorded in the Synoptics and Q document that they are not considered historical. What’s more, critical scholarship overwhelmingly does not consider the seer of Revelation and the author/redactor of the Fourth Gospel to be the same individual. The two have completely different beliefs and writing styles – one, a sophisticated neo-Platonic prose, the other ‘pig Greek’. If the two are the same author, it would be odd that this ‘psychedelic’ John would condemn pharmakeia as a sin that bars one from salvation in his work of Revelation.

Instead of an ecstatic ritual, the communion of bread and wine is depicted throughout the Bible as the menu items of a Messianic Banquet, the “wedding feast” for the imminent coming Kingdom. Paul changed this, with the Fourth Gospel following suit decades later. In line with Greek magical papyri and perhaps his revelations in Arabia (Galatians 1:17), Paul conceived the Eucharist instead as a ‘theophagy’, or the ritual consumption of a god’s body. One wonders why Paul, an apostle so steeped in heretical Greek cultic practice, would then condemn an ostensible psychedelic potion as a step too far. Admittedly, Paul has a mixed relationship with Greco-Roman culture. If the Book of Acts is to be believed, we also hear Paul making use of – but ultimately overturning – the prevailing Stoic and Epicurean philosophies of his day while preaching in Athens.

Muraresku’s citation of Paul is more confused still. He freely sprinkles references to Paul’s female apostles, whom he christens as “witches”. Paul was rarely afraid to condemn his congregants and colleagues. If they were using drugs for the purpose of prophecy, we would hear about it. Muraresku notes Paul’s reference to a “cup of demons” that was ‘apparently lethal’. The passage (1 Cor 10:14-22) is explicitly about idolatry and meat sacrificed to pagan gods. Paul is warning that participating in pagan temple feasts (where food and wine were offered to idols) is incompatible with the Christian Eucharist. The “cup of demons” is a reference to participating in worship of foreign gods, whom early Christians literally conceived as demons. Paul does not make reference to a pharmaceutical problem with such preparations. In the same letter, he even indicated that Christians could consume idolatrous food and drink in order to keep the peace, if it would not damage the faith of others.

Muraresku draws on 1 Corinthians 11:30, where Paul tells the Corinthians that “many of you are weak and ill, and some have died” because they are eating and drinking “without discerning the body.” Muraresku then retrojects this into a pharmacological key, as if Paul were hinting that the prepared “demonic” ergotic wine was toxic. But Paul’s own logic in the passage points in a very different direction. In 1 Corinthians 11:23-29, Paul clearly treats the bread and wine as the sacramental presence of Christ’s body and blood, a site where the believer encounters both judgement and grace depending on their moral and communal disposition. When Paul chastises the Corinthians in 1 Corinthians 11:21, his complaint is not that they are ‘getting smashed’ on psychedelics, but that the rich are getting drunk on ordinary wine while the poor go hungry. It seems strange to us today. But Paul was deadly serious about the association of sin with physical disease. The saving power of Jesus comes from his assumption of a “fleshly”, or sarkic, body, and his subsequent resurrection to a spiritual, or pneumatic, body that lives among the stars.

Relatedly, Muraresku cites the Church Father Ignatius, who wrote that “[t]he Eucharist is the medicine of immortality, the antidote preventing death so that we may live forever in Jesus Christ.” Muraresku presents this as evidence that early Christians understood the sacrament as a sort of drug. He frames it as a “loaded phrase” deliberately chosen for Greco-Ephesians “not quite ready to leave Dionysus behind,” implying Ignatius was nodding to a known pharmacological tradition. Whatever the case, it is clear that Ignatius’s “medicine of immortality” (pharmakon athanasias) is a reference to a theological notion. Ignatius introduces this metaphor earlier in the same letter (Ephesians 7:2), where he calls Christ the “One Physician” who is “both flesh and spirit”.

Christianity emerged from Judaism as well as Greece. Here, the record of entheogenic use is minimal. Second Temple Judaism contains no high-quality evidence of entheogenic ritual practice. Merkabah and Hekhalot mystical traditions – the Jewish mystical frameworks that shaped early Christianity – relied on fasting, prayer, Torah study, and contemplative discipline. Alcohol consumption is both recommended and condemned in the Biblical corpus. The strongest evidence for approved consumption of intoxicating drinks in a worship setting is Deuteronomy 14:26. Israelites are told to spend the money on “whatever your appetite craves,” specifically listing “wine (yayin) and strong drink (shekhar).”

There is also tentative evidence of overlap between Yahwism and the Dionysian religion. Biblical prophets write regularly of the polytheistic and syncretist practices in which the Hebraic people engaged. The Bible captures one slice of the diverse contemporaneous beliefs of the Hebrews. But unless we grant Muraresku’s contention that Dionysian wines were spiked with psychedelic drugs – and that Dionysian syncretists replicated their practices – there is little explicit evidence of psychedelic involvement. Authors at Tel Arad (2020) found traces of cannabis on a Judahite altar (701-586 BCE). “It seems feasible to suggest that the use of cannabis on the Arad altar had a deliberate psychoactive role … to stimulate ecstasy as part of cultic ceremonies”, they write. More work would certainly be helpful to strengthen a persistent psychedelic strain into Christian practice

Some have sought to render entheogenic interpretations of Moses’ theophanies through the burning bush, or the descent of manna in the wilderness. One problem is that both accounts are highly legendary. Among non-fundamentalist scholars, the recollections found in Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Numbers are regarded as largely mythological. Or consider the Yom Kippur service, which explicitly centres on filling the Holy of Holies with dense incense smoke, to the point that some contemporary Jewish writers jokingly describe it as a “holy hotbox.” Even without classic psychedelics, a small sealed chamber filled with thick aromatic smoke, sensory deprivation, fasting, and extreme stress could produce lightheadedness, visions, or dissociative experiences in the High Priest.

There is not much evidence that entheogens shaped Judaism. So their effect on the Jewish sect that became Christianity is likely to be limited, even if some offshoot group consumed drugs.

It is also worth taking some mystical experiences with a grain of salt. In his diagnosis of the “spiritual crisis of the West”, Muraresku briefly treats Paul’s Damascus Road encounter as a paradigmatic mystical event from which religions have become too distant. First, the Damascus narrative appears only in Acts, a late, highly theologised prose romance whose historical reliability is contested; Paul’s undisputed letters never recount the episode in that form, speaking instead of a “revelation in me” without narrative detail. Second, when Paul does discuss mystical experience (2 Corinthians 12:1–7), he locates it firmly within Jewish apocalyptic and merkabah patterns, visions attained through prayer and divine initiative, not technique. In the same section, Muraresku cites the ‘experiences’ of Moses and Muhammad, whose encounters may again be seen as legendary, and with little in common beyond a heavily abstracted category of “mysticism”.

Indeed, the “mystic vs. institution” binary Muraresku relies on collapses when we examine the actual literary foundations of the ‘mystical core’ he champions. The apocalyptic literature of Second Temple Judaism, texts like 1 Enoch and the Book of Daniel, was not the product of raw, anti-institutional experience, but often of highly calculated forgery. The Book of Daniel, for instance, is universally dated by scholars to the Maccabean Revolt (c. 164 BCE) but is written in the voice of a legendary 6th-century exile to authorise anti-Seleucid resistance. This means the “mystical” foundation of early Christianity wasn’t a chemically induced “ego death” or a “religion with no name,” but a sophisticated propaganda tool used by educated elites to assert sectarian authority and delegitimise rival priesthoods. Mysticism was frequently the means by which institutions fought for power.

share your toughts

Join the Conversation.