The usual story taught to children around the world is one of simple categorisation. We are conditioned to view life through a binary lens: Plants & Animals/Flora & Fauna. In this simplified view of the natural world, the mushroom is quite unceremoniously relegated to the kitchen. A passive, silent ingredient we slice onto pizzas or pop alongside our steak and onions. We farm them like crops and view them as a quirky subset of the botanical world.

This is, in fact, a biological falsehood.

Fungi are not plants. They do not contain chlorophyll, and they do not photosynthesise. While plants breathe in carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen, fungi do the opposite. Like animals, they breathe oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. In evolutionary terms, the mushrooms on your plate are more closely related to you than the side salad they are placed beside. They could perhaps be seen as a separate space of biology entirely. A third aspect of the natural world, quietly binding it together.

To understand the scale of the paradigm shift currently reshaping the biotechnology sphere, we must first consider the corresponding scale of the “Kingdom of Fungi”. Scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, estimate that we have yet to discover upwards of 90% of the world’s fungi. We are currently living through what could be seen as a golden age of discovery in this realm. In Kew’s “State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2023”, it describes how over 2500 new species are named and described every year.

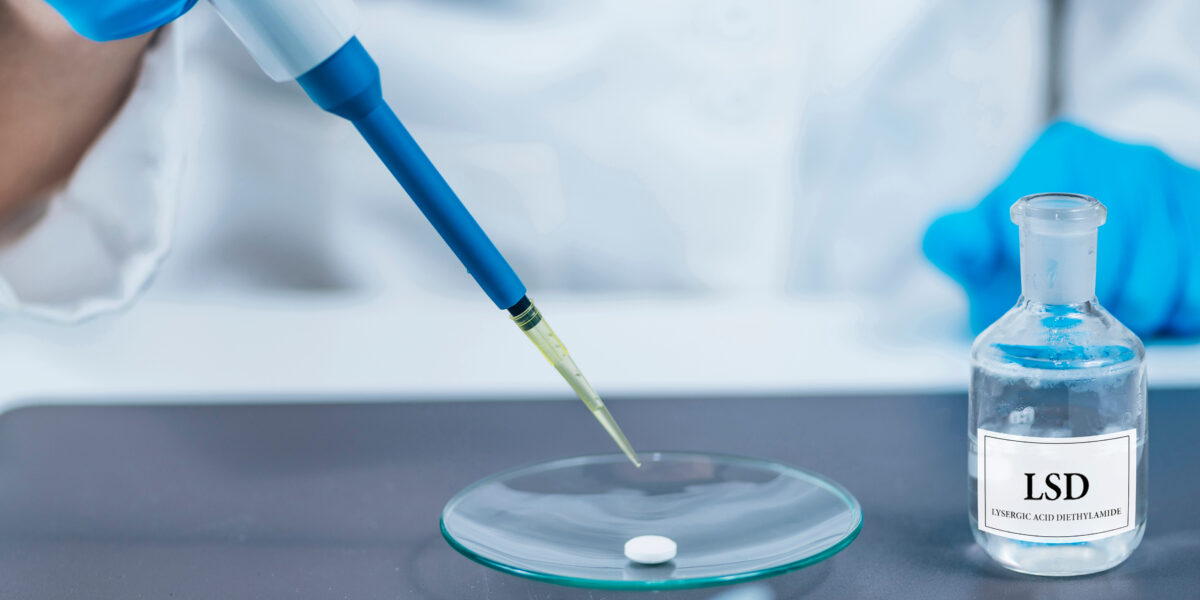

For centuries, our relationship with this hidden kingdom has been limited to the surface. In past cultures, such as the ancient Greeks, fungi were described as “food of the gods”. In more recent history, the 1960s, Western societies embraced them as counter-cultural icons. Psilocybin, like LSD, was just as viable a means to unlock Huxley’s famous Doors of Perception. For the last several years, however, we have begun to realise that we have been looking at the wrong part of the organism. We have obsessed over the bewildering, ever-increasing variety of surface-level “fruit” – ignoring the complexity of the network beneath the soil.

Under every forest floor lies the “Wood Wide Web”. This is a huge subterranean internet of fungal filaments which connects 90% of all plant species. It is this complex architecture that allows fungi to act as the world’s recyclers, builders, and communicators. This process has been integral to life on Earth for millions of years. Before trees even existed, fungi dominated the land. Over 400 million years ago, way before even the dinosaurs existed, the landscape was covered in what are known as Prototaxites, giant spire-like structures that could reach up to eight metres in height and stretch a metre wide. These precursors to fungi were the original architects of the biosphere. We are beginning to see that in the modern age, we may be able to harness this ancient technology as the potential backbone of a more sustainable future.

share your toughts

Join the Conversation.

Never looked at psychedelics this way until now… wow