Aside from China and the Philippines, there are also reports describing an intoxicating mushroom from the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea. The Kuma people of this region ingest mushrooms they refer to as “nonda” (which is a generic term applied to mushrooms), which can evoke “komugl tai” or madness, this being first documented by a missionary in 1936. Intoxication with the mushroom inspires a particular form of traditional dance, primarily consisting of shivering movements. However, in contrast to the previous clear-cut cases pertaining to the Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom being ingested in parts of China and the Philippines, things are far more mycologically murky in this case, for a few reasons.

The Kuma consumed a number of different mushrooms that they attributed to eliciting madness, with multiple species often eaten together as a mixed meal, making pinpointing intoxicating species challenging. There was also strong disagreement among the Kuma themselves about which species is responsible. (Intriguingly, Psilocybe mushrooms are present and known to the locals, but they appear to be considered inedible and avoided.)

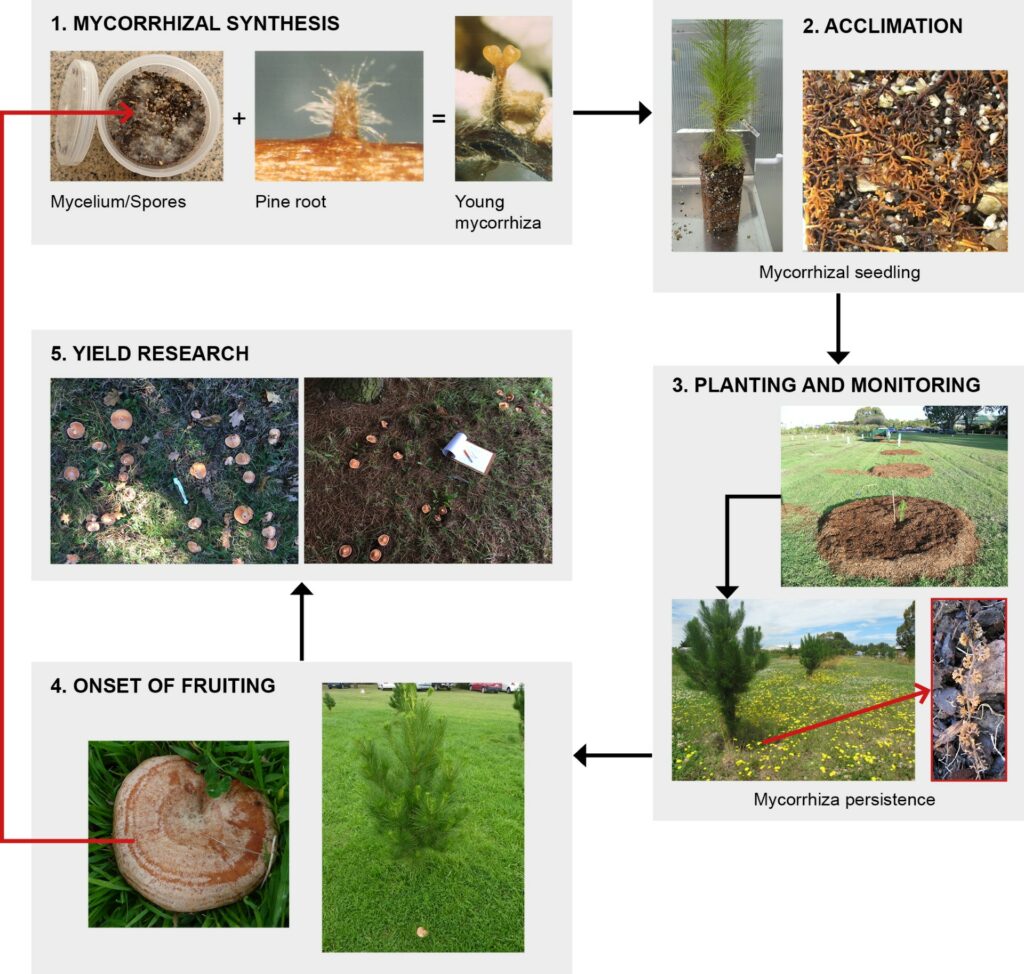

A survey conducted in the region in 2006 suggests that local knowledge of the mushrooms had been lost, with accounts of intoxication events having waned, with a lack of reports since the mid 1980’s. Wild foraged mushrooms have played a diminishing role in the diets of these people over the decades. In addition, those fungi attributed to causing intoxication are all ectomycorrhizal species, often forming mutualistic associations with trees, and accelerating deforestation and climate change in the region may have resulted in a greater scarcity of the mushrooms over time.

The Australian anthropologist Marie Olive Reay undertook an intensive ethnographic study of the “mushroom madness” phenomenon among the Kuma during the mid 1950’s. She estimated that only 10% of the Kuma population that consumed the mushrooms experienced psychic effects, and reported that they recognised four species of intoxicating mushrooms. She observed that symptoms were more common in the final phase of the dry season, and would move from village to village, lasting for 2-3 days. She noted that one person, apparently under the mushroom’s influence, reported encountering little beings, in the form of “bush demons flying about his head”. However, Reay expressed doubts that a mushroom was actually responsible for the effects, instead suspecting that it may have been a form of cultural theatre.

These reports inspired French mycologist Roger Heim and the American ethnomycologist Gordon Wasson to investigate, with Heim collecting mushrooms, and Wasson conducting an ethnomycological survey. Heim and Wasson recorded 12 species of mushrooms indicated by the locals to be responsible for inspiring mushroom madness (including a number of boletes and species of the genus Russula). Chemical testing was conducted on samples of one of these species, Boletus manicus, sent to Albert Hofmann by Heim. Analyses revealed the presence of trace amounts of three indolic compounds. Heim bioassayed tiny amounts of the mushroom on three occasions, reporting luminous, brightly colored visions in a subsequent dream in one instance.

However, due to the inconclusive results of their investigations, Heim and Wasson (like Reay before them) expressed doubts that a mushroom was responsible for episodes of “mushroom madness” reported in the region. They felt it was more likely that claims of “mushroom madness” were more likely a cultural practice of ritualistically and theatrically “acting out”, perhaps functioning as a form of social catharsis. However, ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini has pushed back against this view, stating that the possibility of the involvement of an intoxicating mushroom should not be dismissed.

A 2006 survey conducted at a village in the Western Highlands region reported that only two mushroom species (both Boletus species) were indicated to have intoxicating effects (although B. manicus wasn’t among them). One account was documented of a community elder, likely in his 90s, who described seeing “tiny people with mushrooms around their faces” that were “teasing him” after ingesting mushrooms.

Social anthropologist Henry Dosedla was served cooked mushrooms while hosted by members of the Asaro tribe in the Eastern Highlands Province. His amused hosts offered him a place to sleep, and during his sleep, he described becoming aware of “crowds of tiny warriors of a distinct turquoise colour throwing spears at me and trying to enter my bed”. It is interesting to note that in this case, perceptions of little people occurred during a dreamstate rather than during wakefulness. On waking, his hosts laughed when asking him about his dreams, suggesting that such perceptions appear to be a traditional local feature (also reported among the neighbouring SinaSina tribes). While use of intoxicating mushrooms appears to have been lost among the Kuna, such usage may be widespread in the New Guinean highlands among other groups, including the Kaimbi, Kewa, Gende, Asaro, Sina-Sina, and the Tairora.

Clearly, mushroom intoxication in a Papua New Guinean context remains a little explored frontier. Further work is needed to reveal whether the Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom, or other mushrooms with similar chemistry, are involved, or whether a mushroom is indeed responsible for these past episodes of “mushroom madness” at all.

share your toughts

Join the Conversation.

my guess would be something akin to an anticholinergic, given the true-hallucination, rather than your classic open-eye entoptics/closed eye visuals you get with classical psychedelics… but it seems to lack other features of tropane alkaloids. Would love to see some detailed accounts of full phenomenology, and of course some successful bioassay of the chemical constituents

Interesting